Concurrency control represents the fundamental mechanism that prevents data corruption when multiple threads or processes attempt to access shared resources simultaneously. Without proper synchronization primitives, race conditions emerge, leading to unpredictable application behavior and data inconsistency.

Modern applications increasingly rely on multi-threaded architectures to maximize processor utilization and improve response times. As systems scale, the complexity of managing concurrent operations grows exponentially. Engineers must implement robust synchronization strategies to maintain data integrity while minimizing performance overhead.

The consequences of inadequate concurrency control extend beyond simple bugs. Production systems can experience deadlocks, resource starvation, and silent data corruption. For teams managing distributed systems, implementing effective database monitoring becomes essential to track concurrency-related performance issues across the infrastructure.

Understanding Mutex: Mutual Exclusion Explained

A mutex, short for mutual exclusion, functions as a locking mechanism that allows only one thread to access a critical section at any given time. This synchronization primitive ensures that shared resources remain protected from simultaneous modifications that could compromise data integrity.

The mutex operates on a simple principle: ownership. When a thread acquires a mutex, it gains exclusive access to the protected resource. Other threads attempting to acquire the same mutex must wait until the owning thread releases it. This ownership model prevents multiple threads from executing critical sections concurrently.

Mutexes implement a binary state system-locked or unlocked. The thread that locks a mutex becomes its owner and bears the responsibility of unlocking it. This ownership requirement creates a clear accountability model that helps prevent common synchronization errors.

How Mutex Works in Multi-Threaded Applications

When a thread approaches a critical section protected by a mutex, it first attempts to acquire the lock. If the mutex is available, the thread obtains it immediately and proceeds with execution. The operating system marks the mutex as locked and records the thread’s identity as the owner.

If another thread attempts to acquire an already-locked mutex, the operating system places it in a waiting state. The thread enters a queue and remains blocked until the mutex becomes available. This blocking mechanism prevents busy-waiting, which would waste CPU cycles.

Once the owning thread completes its critical section, it releases the mutex. The operating system then wakes one waiting thread from the queue, allowing it to acquire the lock and proceed. This handoff process ensures orderly access to shared resources while maintaining fairness among competing threads.

Modern mutex implementations often include additional features like recursive locking, which allows the same thread to acquire a mutex multiple times, and priority inheritance, which prevents priority inversion problems in real-time systems.

Understanding Semaphores: Signaling Mechanisms

Semaphores function as signaling mechanisms that control access to shared resources through a counter-based approach. Unlike mutexes, semaphores don’t enforce ownership and can be signaled by any thread in the system, making them more flexible but potentially more error-prone.

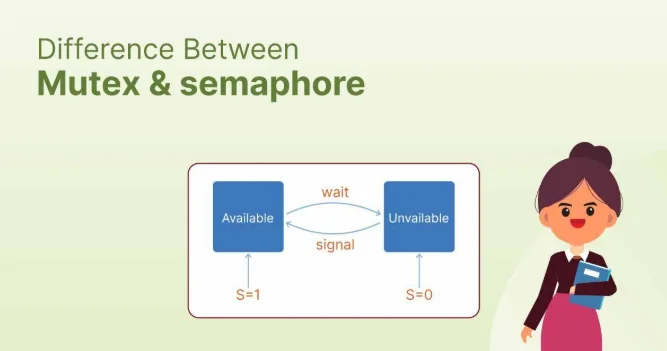

The semaphore maintains an integer counter that represents the number of available resources. When a thread wants to access a resource, it decrements the counter through a wait operation. If the counter reaches zero, subsequent threads block until another thread increments the counter through a signal operation.

This counting mechanism enables semaphores to coordinate access among multiple threads without strict ownership requirements. The flexibility allows one thread to initialize resources while different threads consume them, supporting producer-consumer patterns and other complex synchronization scenarios. Just as semaphores efficiently manage resources in software systems, businesses can manage their digital presence effectively using professional SEO Services London to optimize visibility and performance online.

Semaphores excel at managing pools of identical resources, such as database connections or network sockets. By setting the initial counter value to match the available resources, developers can ensure that no more threads access the pool than resources exist.

Binary Semaphores vs Counting Semaphores

Binary semaphores operate with only two states: zero and one. They function similarly to mutexes but lack ownership semantics. Any thread can signal a binary semaphore, regardless of which thread waited on it. This characteristic makes binary semaphores suitable for signaling between threads rather than protecting critical sections.

Counting semaphores extend the concept by allowing counter values greater than one. The initial value determines how many threads can simultaneously access the protected resource. This multi-access capability distinguishes counting semaphores from both binary semaphores and mutexes.

For example, a database connection pool with ten connections would use a counting semaphore initialized to ten. As threads acquire connections, the counter decrements. When it reaches zero, additional threads block until connections return to the pool and the counter increments.

The choice between binary and counting semaphores depends on the synchronization requirement. Binary semaphores suit event notification and simple signaling scenarios. Counting semaphores better serve resource pooling and throttling use cases where multiple consumers can operate simultaneously.

Key Differences Between Semaphore and Mutex

Ownership represents the most fundamental distinction between mutexes and semaphores. Mutexes enforce strict ownership-only the thread that acquired the mutex can release it. Semaphores impose no such restriction, allowing any thread to signal them.

The purpose differs significantly between these primitives. Mutexes exist specifically to protect critical sections through mutual exclusion. Semaphores serve broader synchronization needs, including resource counting and thread signaling.

Mutexes maintain a binary state tied to ownership, while semaphores use a counter that can represent multiple resources. This architectural difference means a mutex can only be held by one thread, but a counting semaphore can allow multiple threads to proceed based on its counter value.

Performance characteristics also vary. Mutexes typically implement faster operations since they only track binary state and single ownership. Semaphores require more complex bookkeeping to maintain counter values and manage multiple waiting threads.

Priority inheritance mechanisms commonly integrate with mutexes to prevent priority inversion in real-time systems. Semaphores rarely support this feature since they lack clear ownership relationships between threads.

When to Use Mutex Over Semaphore

Critical section protection demands mutex usage. When code must execute atomically without interference from other threads, a mutex provides the clearest semantics and strongest guarantees. The ownership model ensures that the thread modifying shared data also controls when others can access it.

Scenarios requiring recursive locking benefit from mutex implementations. If a function needs to acquire the same lock multiple times before releasing it, recursive mutexes handle this pattern safely. Semaphores cannot support recursive acquisition without additional complexity.

Thread-safe singleton initialization represents an ideal mutex use case. The mutex ensures only one thread creates the singleton instance while other threads wait. Once initialized, the mutex can protect subsequent access to the singleton’s methods.

Data structure protection consistently favors mutexes. Whether safeguarding a linked list, hash table, or custom data structure, mutexes provide intuitive semantics. The lock-modify-unlock pattern clearly communicates intent and prevents race conditions.

When debugging concurrent code, mutexes offer advantages through ownership tracking. Development tools can identify deadlocks and improper unlock operations more easily with mutexes than with semaphores. This visibility accelerates troubleshooting in complex systems.

When to Use Semaphore Over Mutex

Resource pool management naturally suits semaphores. When limiting concurrent access to a fixed number of identical resources, counting semaphores provide elegant solutions. Database connection pools, thread pools, and network socket pools all benefit from semaphore-based throttling.

Producer-consumer problems demonstrate semaphore strengths. Multiple producers can generate work items while multiple consumers process them, with semaphores coordinating buffer access and signaling data availability. This pattern appears frequently in message queues and pipeline architectures.

Rate limiting implementations leverage semaphores effectively. By controlling the semaphore counter, applications can throttle operations to prevent resource exhaustion. This approach works well for API rate limiting, disk I/O throttling, and network bandwidth management.

Cross-process synchronization scenarios favor semaphores in some operating systems. Named semaphores can coordinate processes that don’t share memory, enabling inter-process communication patterns that mutexes cannot support without additional mechanisms.

Event notification between threads benefits from binary semaphores. When one thread must signal another about condition changes, semaphores provide lightweight notification without the overhead of condition variables or the ownership constraints of mutexes.

Common Mistakes in Concurrency Control

Forgetting to release locks represents the most prevalent error in concurrent programming. When threads acquire mutexes or wait on semaphores but fail to release them due to exceptions or early returns, deadlocks occur. Always use RAII patterns or finally blocks to guarantee release operations.

Lock ordering inconsistencies cause deadlock situations that plague production systems. When thread A acquires mutex X then mutex Y, while thread B acquires mutex Y then mutex X, circular dependencies emerge. Establishing consistent lock ordering across all code paths prevents these deadlocks.

Using semaphores where mutexes belong introduces subtle bugs. Since semaphores lack ownership, nothing prevents a different thread from accidentally signaling a semaphore that protects a critical section. This mistake violates mutual exclusion guarantees and corrupts shared data.

Insufficient granularity in locking strategies hurts performance. Holding locks longer than necessary creates contention and reduces parallelism. Conversely, overly fine-grained locking increases complexity and overhead. Finding the right balance requires profiling and iterative refinement.

Ignoring priority inversion in real-time systems leads to unpredictable behavior. When a low-priority thread holds a mutex needed by a high-priority thread, the system can miss deadlines. Priority inheritance mutexes solve this problem but require explicit configuration.

Performance Implications: Mutex vs Semaphore

Mutex operations typically complete faster than semaphore operations due to simpler state management. The binary nature of mutexes allows operating systems to optimize lock acquisition and release paths. Modern implementations use atomic operations and futexes to minimize context switches.

Cache coherency affects both primitives but manifests differently. Mutexes concentrate contention on a single memory location, potentially causing cache line bouncing between processor cores. Counting semaphores spread contention across counter management and wait queue operations.

Context switching overhead dominates performance costs in highly contested scenarios. When many threads compete for the same synchronization primitive, frequent context switches degrade throughput. Both mutexes and semaphores suffer from this effect, though the severity depends on implementation details.

Spinning versus blocking strategies influence performance characteristics. Spin locks waste CPU cycles but avoid context switch overhead for short critical sections. Blocking mutexes conserve CPU but incur switching costs. Adaptive approaches combine both strategies based on contention levels.

Memory ordering requirements impose performance penalties on all synchronization primitives. Both mutexes and semaphores require memory barriers to ensure proper ordering of loads and stores. These barriers prevent compiler and processor optimizations that could reorder operations unsafely.

Best Practices for Thread Synchronization

Minimize critical section duration to reduce contention and improve throughput. Move expensive operations like I/O or memory allocation outside protected regions whenever possible. Only the minimal data structure manipulations should occur while holding locks.

Use read-write locks when workloads exhibit high read-to-write ratios. These specialized primitives allow multiple readers to proceed simultaneously while ensuring exclusive access for writers. This optimization can dramatically improve performance for read-heavy data structures.

Implement lock-free algorithms where appropriate to eliminate synchronization overhead entirely. Atomic operations and compare-and-swap instructions enable concurrent data structures without traditional locks. However, lock-free programming introduces complexity that requires careful design and testing.

Document locking protocols explicitly in code comments and design documentation. Clear documentation helps maintainers understand lock ordering requirements and prevents introduction of deadlock-prone changes. Include rationale for specific synchronization choices.

Profile concurrent code under realistic workloads to identify bottlenecks. Theoretical analysis only goes so far-actual contention patterns depend on timing and load characteristics. Tools like thread sanitizers and lock profilers reveal hot spots that need optimization.

Consider alternative concurrency models like message passing or software transactional memory for complex systems. Traditional lock-based synchronization becomes unwieldy as complexity grows. Higher-level abstractions can simplify reasoning about concurrency while maintaining correctness.

Monitoring Concurrency Issues in Production Systems

Detecting concurrency problems in production requires specialized monitoring tools and metrics. Track lock acquisition times, hold durations, and contention rates to identify synchronization bottlenecks. Sudden increases in these metrics often indicate performance degradation or deadlock conditions.

Deadlock detection mechanisms should run continuously in production systems. Many runtime environments provide deadlock detection APIs that periodically check for circular wait conditions. Automated alerts notify operations teams when deadlocks occur, enabling rapid response.

Thread dump analysis reveals blocking relationships and lock ownership during incidents. When performance degrades, capturing thread dumps shows which threads hold locks and which threads wait for them. This visibility helps diagnose deadlocks and contention issues.

Distributed tracing extends to synchronization primitives in sophisticated monitoring platforms. By tracking lock acquisition and release events, engineers can visualize synchronization behavior across service boundaries. This capability proves invaluable for debugging microservice architectures.

Performance regression testing should include concurrency-specific test cases. Automated tests that measure throughput under various contention scenarios catch performance degradation before production deployment. Continuous benchmarking maintains visibility into synchronization overhead trends.

Error budgets for lock contention help teams prioritize optimization work. By setting acceptable thresholds for lock wait times and contention rates, organizations can quantify when synchronization becomes a problem requiring investment. This data-driven approach prevents premature optimization while ensuring performance remains acceptable.